Updated Exhibition of the Sepa Farmstead

In May 2025, the Sepa farmstead, which had previously depicted the life of a village blacksmith from South Estonia at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, was transported into the early 1950s – the initial years of collective farming, specifically to the year 1952, a dark and difficult time on the eve of Stalin’s death.

The multi-apartment collective farmhouse at the Estonian Open Air Museum, along

with its outbuildings and yard, mainly represents the 1970s – a time when

collective farms had become established and were operating relatively well.

This Soviet-era building focuses primarily on the apartments and daily life of

their residents rather than on political history in the direct sense. Both

rural and urban visitors will find something familiar here.

Unfortunately,

through the lens of the apartment building, the Soviet period had been depicted

one-sidedly, which gave rise to a new “untold story” – the need to also speak

about the early years of Soviet collective farms, collectivization as a

destroyer of former rural life and sense of ownership, deportations, forced

decisions, fears and hardships of the early collectivization years, the gap

between cynical propaganda and harsh reality, and the collapse of the previous

way of thinking and living.

To

tell this complex and ambiguous story, the former village blacksmith becomes a

collective farm blacksmith, and he must adapt to life under new conditions. The

interior exhibition and the surrounding yard at Sepa farmstead allude to the

phenomena characteristic of these difficult times. In video clips shown in the

smithy and the farmhouse, the current situation is conveyed through the fate of

Jaan Harak, who was once a village blacksmith and became a collective farm

worker. Attentive visitors will notice other hidden clues as well. Although

Sepa farmstead offers a general cross-section of the era, much of what is shown

is based on the real history of its former inhabitants – the Harak family.

There are three buildings in the spacious yard of Sepa farmstead: a dwelling combined with a cowshed built between 1880 and 1890, a sauna, and a smithy. The changes primarily affect the yard, as well as the farmhouse and the smithy.

Along the route leading to the apartment building of the Estonian Open Air Museum, the new exhibition at Sepa farmstead provides the most complete insight into and understanding of forced collectivization in Soviet Estonia.

The concept of the Sepa farmstead exhibition was developed within the framework of the research project “Changes in Rural Life and Everyday Living in the Estonian Countryside during the Early Years of Collective Farming,” financed by the Ministry of Culture’s sectoral research and development budget. The creation of the exhibition is also supported by the Eesti Kultuurkapital (Cultural Endowment of Estonia).

From the history

Craftsmen’s farm of the turn of the 20th century

Sepa farm from Rõuge parish represents the household of a blacksmith in southern Estonia at the turn of the century. Brought to the museum in 1987–1997 and opened for visitors in 1999.

This small farm in Võru County had some 10 ha of poor soil, and smithcraft was the main source of income. Due to the changes in the economy of Estonia in the second half of the 19th century, rural handicraft developed at a fast pace. The amount of work for the village blacksmith from a long line of tradesmen also increased because farms started using better steel farming tools and machines. So the farm owners of Palometsa village who were interested in getting themselves a good blacksmith helped him set up Sepa farm by giving the logs for the buildings.

The shed dwelling was built in 1880s–1890s (the cattle shed part is newer) on Sepa farm in Palometsa village, Rõuge parish of Kasaritsa commune. It was brought of the museum in 1987. The entrance hall of this small dwelling that belonged Peep Harak, a former blacksmith of Sänna manor, and his wife Liisa, a manor maid, opens to the pantry and the kitchen, from which we get into a narrow chamber. The outbuilding constructed next to the house has enough space to fit a small cattle shed for a cow and a sheep, a tiny pigsty and the space in between that was used for storage.

The sauna was also brought from Sepa farm, Palometsa, in 1987. The small smoke sauna consists of the anteroom and the steam room, where water can be heated in a big pot on the sauna oven with heating stones.

The smithy was brought from Kasaritsa commune, Rõuge parish, which is now the town boundary of Võru. The period of its construction is unknown. Jaan Mõõk from Vastselinna relocated the log building to a place on the road to Võru from some nearby neighbourhood at the beginning of the 20th century. He was famous for horse shoeing and used to shoe army horses but would never refuse to work on carts or sleds. Jaan Mõõk usually apprentices and demanded good work.

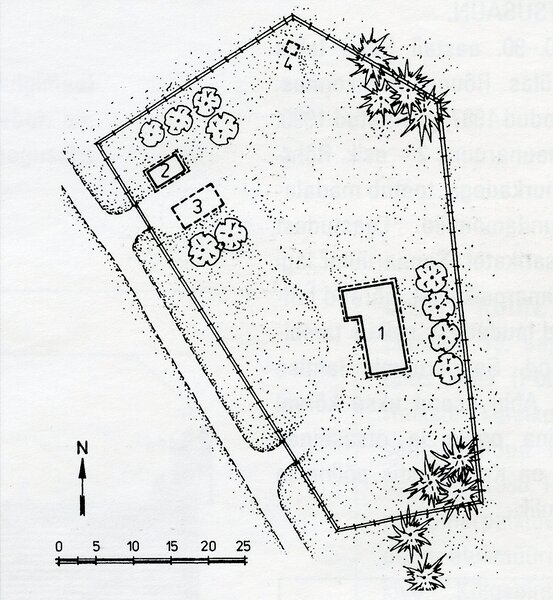

Farmyard plan

1 – shed-dwelling, 2 – sauna, 3 – smithy, 4 – wellDid you know?

- Craftsmen often came from small farms or families that did not have any land. Blacksmith Peep Harak was apparently the youngest son of the family of Isaku farm in Palometsa.

- Jaan Harak, Peep Harak's son, became a tradesman too. He was good at smithcraft and pottery, could build a use and sew a suit and was also the village doctor.

- Before people had to bring their own iron and coals to the smithy and pay the blacksmith in foodstuff, but in the 20th century blacksmith received money for their work.